A Car in the Garage, A Computer on the Desk

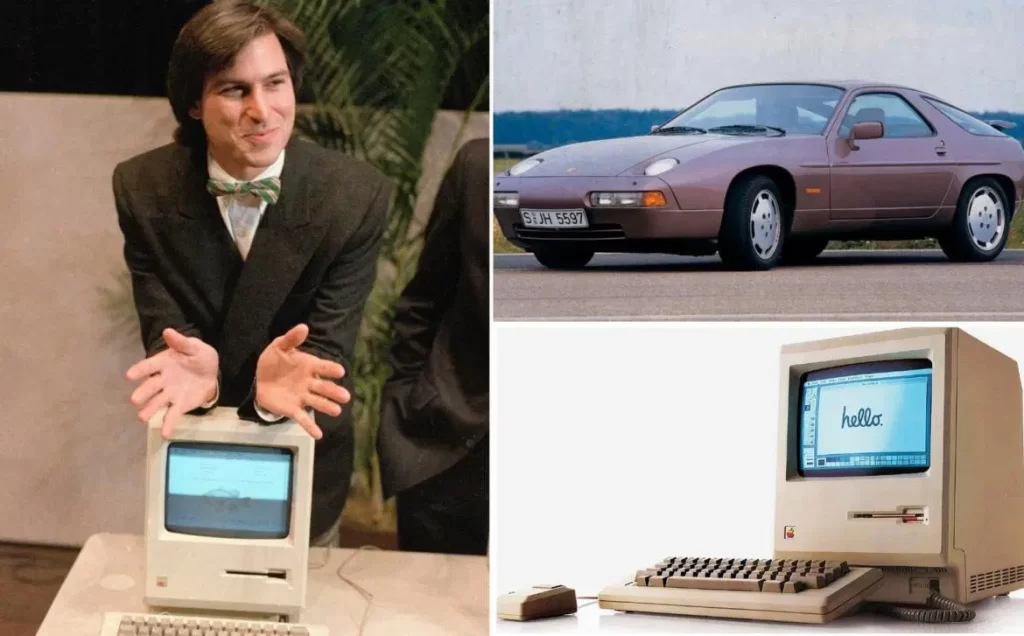

In the early 1980s, Steve Jobs was already shaping Apple’s identity as much through design as through technology. At a late-night design review in March 1981, the future of the Macintosh was laid out on a prototype table. Apple’s director of creative services, James Ferris, casually compared the shape to a Ferrari. Jobs shook his head. “Not a Ferrari… it should be more like a Porsche,” he insisted, according to Andy Hertzfeld’s account on Folklore.org. For Jobs, the object of comparison was not theoretical. Sitting in his garage at the time was a silver Porsche 928, a car whose flowing curves, flush panel gaps, and seamless integration of form and function had captivated him. He wanted nothing less for the machine that would introduce Apple to the mainstream.

Steve Jobs and Wozniak

The Porsche 928 was not just another sports car. Launched in 1977, it was revolutionary: Porsche’s first with a front-mounted all-alloy V8, marrying hatchback practicality with the refinement of a grand tourer. Its clean belt line, body-colored bumpers, and pop-up “shark eye” headlamps shocked purists but won accolades, including the coveted European Car of the Year in 1978. It remains the only sports car to claim that honor. Jobs saw in the 928 a purity of design that promised timelessness, and he wanted the Macintosh to carry that same promise into computing.

Jobs emphasized the 928’s attributes that mattered most to him: its cohesive surfaces, tight tolerances, and absence of unnecessary flourishes. He urged the design team to pursue a look that would never go out of style, a computer case that could stand on a desk for years without appearing dated. The Mac, like the 928, was meant to be more than a tool. It was meant to be an enduring object of design.

From Silver Shark to Beige Toaster

Translating the spirit of a Porsche into the form of a computer required discipline. Jobs worked closely with industrial designer Jerry Manock and drafter Terry Oyama, pushing for a vertical, all-in-one layout with the display stacked above the floppy drive to conserve desk space. He rejected Jef Raskin’s earlier “lunchbox” concept and demanded softer edges and more curvature, scrutinizing plaster models for bezel radii the way a car designer studies fender lines. The Macintosh, he declared, had to be curvaceous, not boxy, a philosophy lifted directly from the 928’s sculpted bodywork.

The design details reflected that ethos. The Macintosh 128K launched in 1984 without a cooling fan, a controversial decision Jobs defended on the grounds of refinement. He wanted it to run silently, just as the 928 cruised quietly as a grand tourer. A molded carry-handle was built into the plastic case, echoing the 928’s hatch cut-out, which made it easier to lift and load. Even the unity of the Mac’s case design, with its uninterrupted lines, mirrored the 928’s belt line. Jobs reinforced the artistry of the machine by having all 47 members of the Mac team sign the interior of the case. “Real artists sign their work,” he insisted, embedding craftsmanship into the object itself.

The trade-offs of these design choices were real. The fanless case caused overheating, earning the Macintosh the enduring nickname “the beige toaster.” But just as Porsche purists derided the 928 for breaking with tradition, only to see its styling age gracefully, the Macintosh’s compact, seamless form set a new standard. Both the car and the computer endured criticism, yet both would be remembered as icons of design discipline and bold departures from convention.

Icons Born from Bold Design

When the Macintosh 128K finally launched in January 1984, Apple unveiled it with the Ridley Scott–directed “1984” commercial, one of the most famous advertisements in history. The campaign cost up to $900,000 to air but recouped its investment almost instantly, with $3.5 million worth of Macs sold in the first weekend. In its first 100 days, the Macintosh moved 72,000 units, surpassing Jobs’ internal target of 50,000. But momentum slowed after the rush of early adopters, mirroring the trajectory of the Porsche 928. Celebrated at launch, sales cooled once the novelty wore off. Both became modest performers in their categories, yet their influence endured long after the numbers faded.

The Macintosh introduced a graphical user interface, mouse-based input, and a philosophy of user-friendly design that still underpins macOS today. Likewise, the Porsche 928, once dismissed for its unorthodox front-engine layout, is now celebrated among collectors for its engineering, refinement, and timeless styling. The flush glazing, integrated bumpers, and curving proportions that defined it continue to inform modern automotive design, just as the Macintosh’s compact, all-in-one silhouette defined the desktop computer.

Jobs’ decision to model a computer after his sports car was never about literal translation but about ideals: timeless proportions, integration of form and function, and details that reward close inspection. Today, an original Macintosh 128K, particularly one bearing the signatures of its creators, is treasured as much for its industrial design as for its technological place in history. A well-preserved Porsche 928, too, commands respect not simply as a machine, but as an artifact of design philosophy. For Jobs, the line between the two was always clear: great products, whether mechanical or digital, should be as beautiful as they are functional.